Curating Fascism by Sharon Hecker

Author:Sharon Hecker

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing

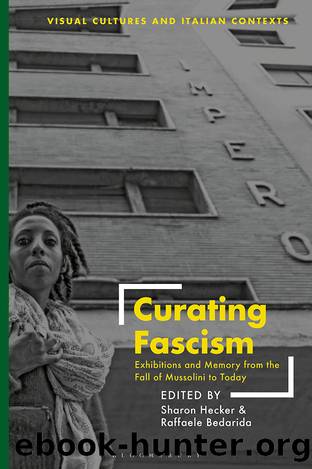

Figure 10.5 Installation view, Chaos and Classicism Art in France, Italy, and Germany 1918 to 1936, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, October 1, 2010âJanuary 9, 2011. Photograph by David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

This explicit overcoming of historical elaboration was continued with the inclusion of Pontiâs urns and cists in Anni Trenta: Arti in Italia oltre il Fascismo, a 2013 show in Florence that extended Ragghiantiâs seminal exhibition of 1967.21 There an urn and a blue-and-gold bowl from the series I trionfi (c. 1930) presented a variation on forms already seen, which accentuated the use of ancient Roman iconography in the construction of the visual mythography of fascism. The interpretative key attributed to Ragghianti for the 1967 exhibition, which overcame postwar polemics with a Crocian vision centered on the quality of artistic products, was adopted in this exhibition. In particular it integrated a number of decorative objects, which provided an overview of the production of the period but failed to address critical elementsâfascist iconography, for exampleâexcept by providing an objective datum: âThe exhibition proposes an approach according to the perspective of the time,â declared the curators, âthat is to say that we have endeavored to restore how the critics of the time considered the art of the 1930s, in order to try to free ourselves from the prejudices we have about this historical period.â22

The almost complete series of Pontiâs vases from the 1920sâthe Passeggiata archeologica, La conversazione classica, and Mani della Fattucchieraâwere also found in the 2015 exhibition at the Musée dâOrsay, Dolce Vita? Du Liberty au Design Italien (1900â1940), which constituted a further departure from the critical examination of history.23 Based on recent acquisitions, the exhibition stemmed from the proposition that Italian decorative arts from the beginning of the century to the outbreak of the Second World War are characterized by a joyful vein, which becomes more pronounced as one approaches the néant.24 Although the shocking image of the corpses of Mussolini and his lover Clara Petacci on display in Piazzale Loreto can be found in the catalog, the selection of pieces of the highest level celebrates the decorative arts as evidence that the world of design was âduring the period of fascism in Italy the unique domain in which subsisted a real, veritable free will.â25 Pontiâs ceramics, together with Paolo Veniniâs glass, de Chiricoâs paintings, and the hybrids of Enrico Prampolini and Nikolay Diulgheroff present a formal and technical quality that was associated preemptively with âMade in Italyâ as the bearer of aesthetic values and good taste after the warâan assertion that completely disregards the historical framework in which Italian design was born. The objects, rather than the paintings or plastic works, were presented as the products of a lack of awareness on the part of the bourgeois and upper classes of Mussoliniâs brutality.

A similar attitude pervaded the rooms of the Fondazione Prada in 2018, where Pontiâs urn with motifs of the Passeggiata archeologica appeared once again, and, in front of a 1920 Prampolini tapestry, the large vase Casa degli efebi.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Belgium | France |

| Germany | Great Britain |

| Greenland | Italy |

| Netherlands | Romania |

| Scandinavia |

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(5136)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4825)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4792)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4370)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4228)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4121)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(4015)

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe(3993)

I'll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson(3455)

Shadow of Night by Deborah Harkness(3382)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(3355)

Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Murder of Lord Darnley by Alison Weir(3220)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3210)

Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell(3190)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(3138)

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography by Thatcher Margaret(3090)

Book of Life by Deborah Harkness(2947)

Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine by Anne Applebaum(2942)

The One Memory of Flora Banks by Emily Barr(2872)